Your Concise Guide to Containerisation

The world of international trade we know today is highly dependent on one, seemingly simple, component – the shipping container. Here’s what you need to know about it in a nutshell:

The history of the shipping container

Before the invention of containerisation in 1957, goods were typically transported in bales, barrels, crates, or sacks. These had to be loaded onto cargo ships by hand which took weeks and required considerable manpower.

A still-standing ocean carrier is not profitable, so shipping providers were thrilled to assimilate containerisation – a system whereby their cargo vessels could dock, unload, and re-load within a matter of hours. This system is the brainchild of Malcom McLean who owned a large trucking company in Northern America up until the 1950’s.

The containers McLean patented were lockable, durable, and stackable. Most importantly, they could be stuffed (loaded) in advance and then only taken to the ship at the time of loading. A container could then be hoisted onto the ship using a crane without so much as touching its contents. This greatly simplified the process of transferring cargo from trains and trucks onto shipping vessels as well as unloading at the destination port.

McLean bought a shipping line in 1955 and, using containerisation, cut the cost of cargo transport by 25%. Demand soon led leading logistics companies to adapt their vessels, depots, and railway sidings to containerisation too. Naturally, ports around the world followed suit by providing the infrastructure their clients needed.

The basic shipping container

To uphold its efficiency container transport requires standardisation in terms of the size, shape, and durability of containers. There are however still a variety of containers available to international traders.

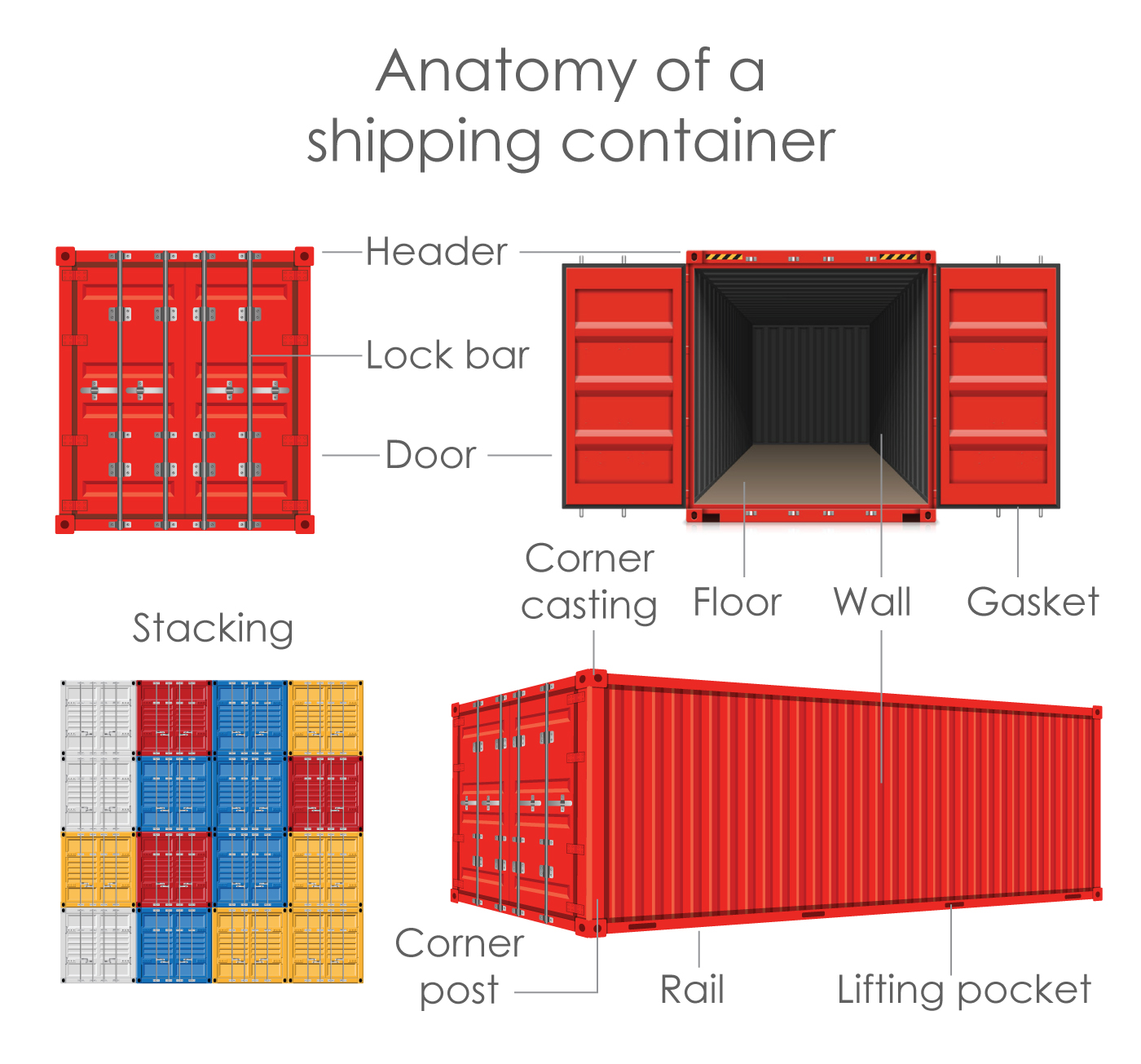

The stock standard container, also referred to as the dry storage container, consists of a laminated plywood floor and three walls, a roof, and a water-proof door all made of primed steel. These versatile containers are available in 40ft and 20ft sizes. The 40ft size is available in a standard height of 2.6m and a “high cube” which is 30cm higher, but otherwise the same.

Although a 10ft dry storage container exists, it is rarely used for international shipping.

A popular adaptation of the dry storage container is the tunnel container, which has a door on either short side.

Other types of shipping containers

Flat rack container – A base with collapsible panels on the short sides and no side walls. Used for large goods (like machinery) that would not fit within the walls of a conventional container.

Open top container – A standard container with a convertible roof that can also be completely removed. This is ideal for a shipment whose height prevents it from fitting in a conventional container. The goods are generally covered with a tarpaulin.

Open side / Double door container – Features an additional door in one of the side (long) walls for ease of loading.

Half-height container – Half the height of a standard container and often open-topped. Used mostly for heavy, non-breakable cargo like coal and stones.

Insulated / Thermal container – Comes with regulated temperature control allowing a higher temperature to be maintained.

Refrigerated / Reefer container – A container that self-regulates internal temperature. Used for perishable shipments, like fruits and vegetables, over long distances.

ISO Tanks – Storage units used for transportation of liquid materials. The tank is built into a bracket which allows for stacking.

Car carriers – Container storage units made especially for the shipment of cars. Collapsible sides help a car fit snugly inside the container and secure it in place to prevent damage.

FCL vs LCL shipping

Whether or not you’ll ever see your container depends on whether your shipment warrants a full container load (FCL) or less than a container load (LCL).

FCL shipments

If your goods are enough to fill a container, your freight provider will most likely arrange for a truck to bring an empty shipping container to your premises. The container is then stuffed, sealed, and kept at a container depot until it is time to load the ship.

A FCL shipment consigned to you will be delivered by truck to be unpacked at your premises.

FCL shipping is the ideal scenario in terms of security and the well-being of your goods as there is nothing in the container you don’t have control over. Per unit of volume, FCL is also more affordable as there is less handling involved.

FCL shipping is significantly faster than LCL as there is no consolidation or de-consolidation of your cargo required. The difference in delivery time can be as much as 10 days. Traders often book an FCL shipment purely because this time benefit makes more financial sense than saving on delivery costs. As neither the trader nor the freight forwarder is obligated to fill the container, an FCL shipment can be loaded whether the container is stock-full or contains a single pallet.

The drawback of FCL is that, once your container arrives, you have a limited timeframe in which to stuff or unpack it. Any delays in doing so will hold up the truck the container is on and may incur additional charges from your freight provider.

LCL shipments

If your shipment is less than a container load (LCL) your freight provider may require that you bring the goods to a container depot to be consolidated with other shipments. You can also arrange for it to be collected.

Goods from various traders are then used to fill a container consigned to the freight provider’s associate at the port of import.

Once the goods arrive the container is unpacked (deconsolidated) and the various shipments are made available to the importers. As mentioned above, this consolidation and de-consolidation process significantly delays the delivery of your goods compared to an FCL shipment.

LCL shipping is cheaper but carries risk in that you have little control over what goods your shipment will be exposed to. If you are, for example, shipping textiles, there is a risk of it assimilating a smell from the other traders’ goods. Airtight packing can prevent the majority of risks involved with LCL shipping but cannot guarantee anything. If you are booking an LCL shipment, be mindful that your cargo insurance covers this type of damage to your goods, not just total loss.

The risks of containerisation

Although using shipping containers makes international trade practical and affordable, it is not without risk. The major concerns are as follows:

Inherent vice

Cargo insurance as a rule excludes inherent vice. This refers to damage that occurred to a shipment due to something that was already present when it was packed.

Inherent vice with containerisation can come in the form of bugs or rodents that entered a container with, for example, a load of grain. It can also be moisture that was trapped in wet wooden pallets that causes a consignment of machinery to corrode in transit.

Because shipping containers are sealed for the duration of a voyage, you won’t be aware of the inherent vice until it is too late to do anything about it.

Discrepancies with seals

Once a container is stuffed it is fitted with a uniquely numbered seal. The number of the seal is noted on the bill of lading, so the consignee has assurance that the content was not tampered with in transit.

If your shipment is stopped at customs for an inspection, you or your freight forwarder have the right to be present when the container’s seal is cut and to supervise the inspection, so you will be made aware of this. If you receive a container with a seal number that does not match your documentation do not open it. Contact your freight forwarder to first determine where the seal was presumably cut and replaced, and why.

Only once the matter is resolved can you cut the seal and unload your goods.

Expensive inspections

Customs authorities reserve the right to do documentary and/or shipment inspections on any import or export.

With a shipment inspection, the cargo must be taken to a bonded facility to be viewed by a customs officer. In the case of a containerised shipment, this would be a container yard. You or your freight agent must then make an appointment for the inspection. The additional costs that will be billed to you for the sake of this inspection are:

-

- Storage of the shipping container at the depot

- Transport to get the customs officer to the depot

- Unloading the goods for the sake of the inspection

- Reloading of the goods after inspection

- Potentially a fee from your freight agent if they oversee on your behalf

Container damage

Containers require regular maintenance. If this is neglected there is a risk of water damage to your shipment which, again, would not be insured.

Here are key checks you should do before loading a container:

Penetrating rust – Rust on the surface of a container wall is not a concern. You should however be cautious of rust that penetrates the top layer of metal. Tap the rusty area with a hammer. If chunks fall off there is a risk of leakage. Remember to check the roof and the doors. The bottom of the doors is especially a hotspot for rust.

Holes – Ask someone to close the container doors while you are inside so it is completely dark. While inside, check for spots where you can see light coming in – these are holes that would also allow water to damage your shipment.

Door and locks – Test the doors to ensure the gasket is in good order, that they open and close completely (1800), and that the locks latch properly. You don’t want to discover that you can’t lock your container once it is already loaded.

CSC plate – All active shipping containers must go to a container depot for quality and durability inspection at least every 30 months. The inspection approval (ACEP), owner’s information, and technical details of the container appear on the CSC plate which you can find affixed to the outside of the door.

If you are dissatisfied with your container, it is within your rights to refuse it and ask your freight provider to send another one.

Need a freight agent you can trust? Contact us and we will get you in touch with our network of skilled and helpful freight providers.